Spraying glaze is a fairly complicated process. There are craftspeople in Jingdezhen whose only job is going from workshop to workshop spraying glaze. There are so many factors involved with spraying (the type of work, thickness of work, type of glaze, glaze consistency, air pressure, spray head type, even weather) that it requires years of experience to be able to master the art.

I hope to slowly add to this article in the future. For now I will just lay out the basics of how I spray glaze.

The Spraying Booth

My spray booth is made locally in Jingdezhen. It’s a simple stainless steel frame with glass. A large fan is attached to the back, sucking out particles. Water is pumped from a bucket through a hose that leads to the top of the booth interior. The water is channelled along the top of the glass and then exits through small holes, forcing the water to run down the glass, washing away glaze. The water finally exits through a hole in the bottom of the spray booth, pouring back into the water bucket.

A typical Jingdezhen spray booth

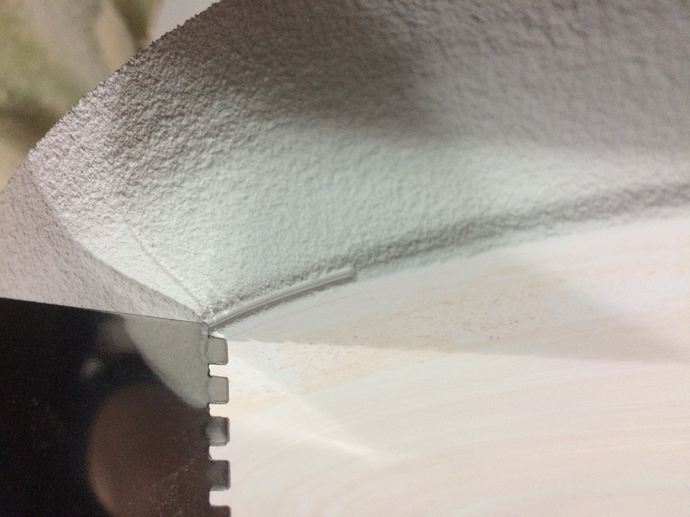

A gap between glass and stainless steel reservoir evenly distributes water down the glass.

The fan at the back of the spray booth blows out particles.

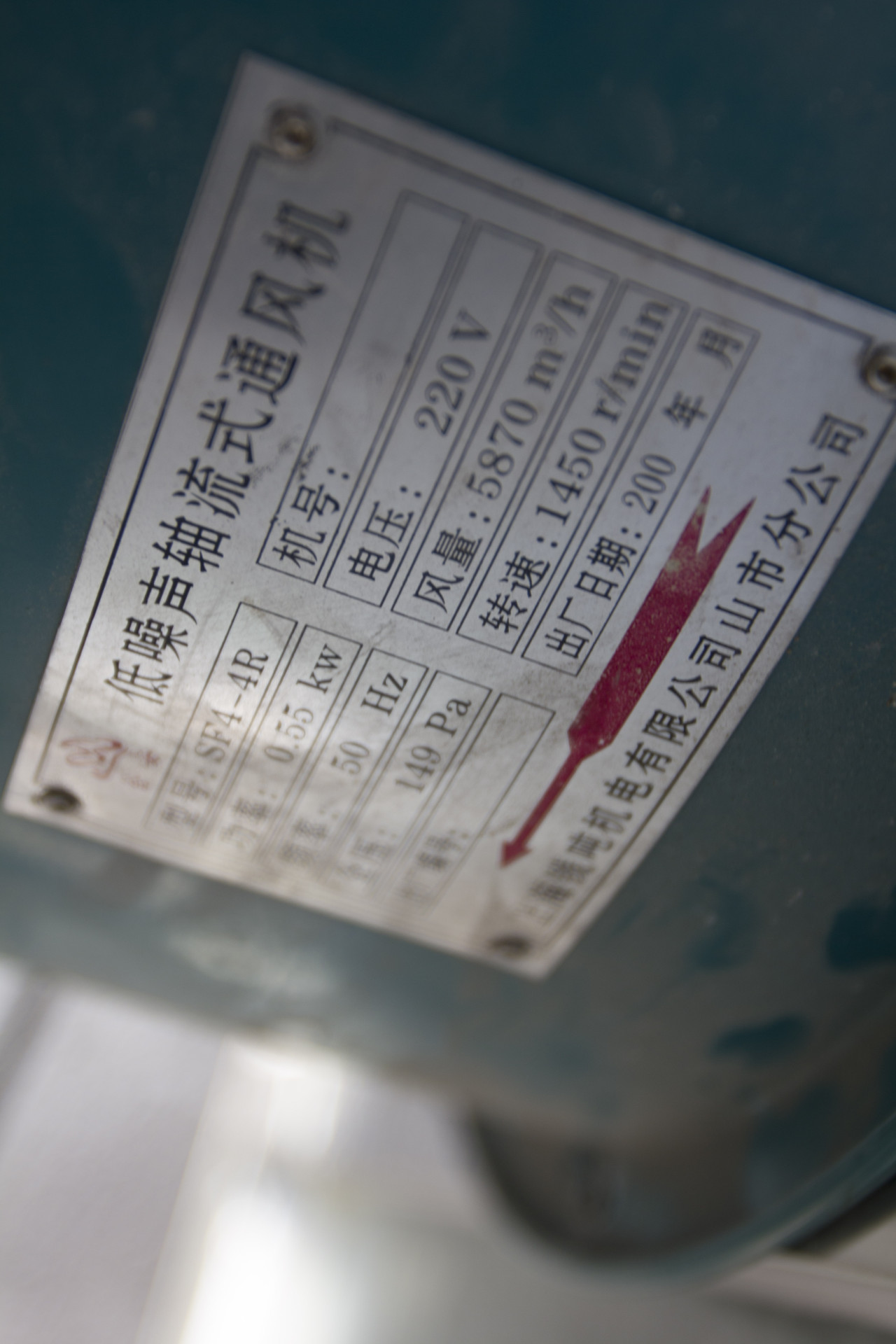

Detail of the fan label

The pump sucks water from a bucket and up through the spray booth.

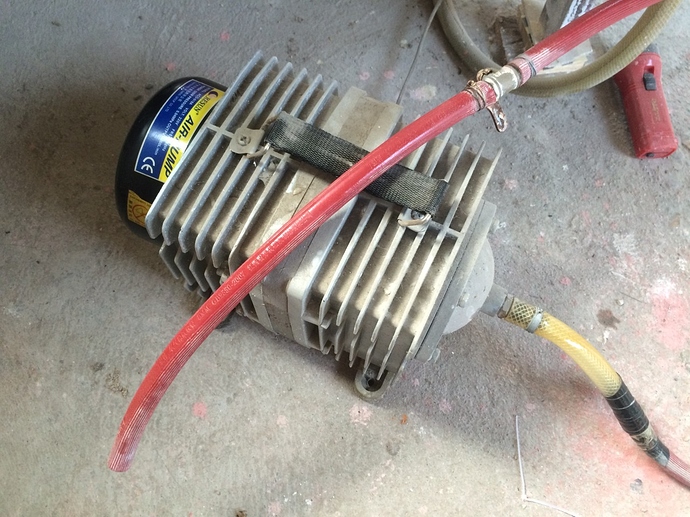

Detail of the water pump

Inside the booth I place a large plastic basin for collecting glaze. Inside the basin is a turntable.

On top of the turntable I place a plaster disk. The added weight results in more even turning, while the plaster absorbs glaze. A notch in the plaster helps with counting revolutions. After spraying, glaze can be scraped off and collected.

The Air Compressor

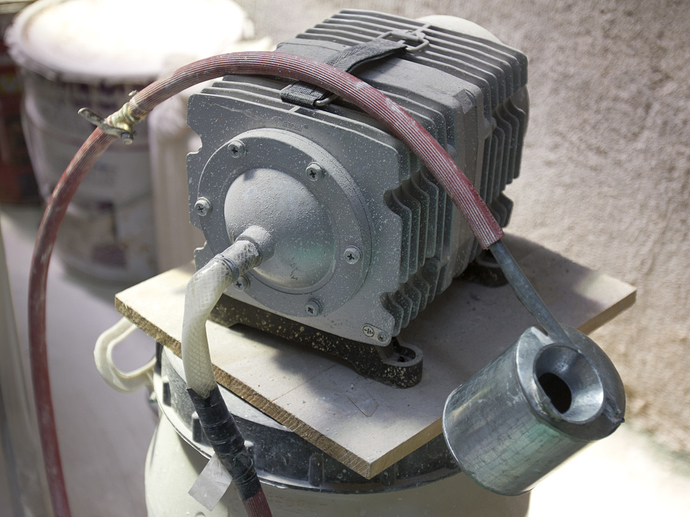

I have an old, noisy air-tank compressor that I rarely use. I much prefer the Jingdezhen method- a cheap magnetic air compressor used in fish tanks. I’ve used my current compressor for six years and it still runs great, with no need to worry about adding oil or filtering the outgoing air.

I’ve found that a 520W compressor is ideal. In the past I had a smaller compressor that didn’t spray as well.

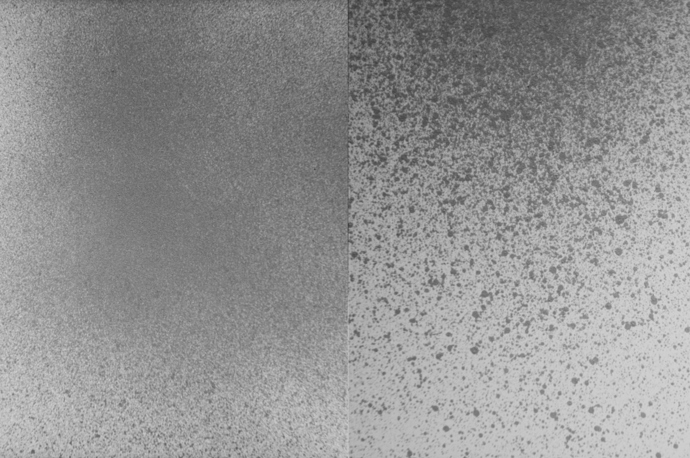

The sprayer does a great job of mimicking traditional Jingdezhen glaze spraying using just the breath. A normal air compressor using a paint sprayer head will give you a finely atomized cloud of glaze resulting in a powdery glaze application. But a traditional mouth sprayer connected to the fish tank compressor will give you relatively large glaze droplets that soak into the clay, leaving a more compact glaze application.

The fish tank compressor method also sprays less glaze into the air. I often just run the water pump and leave the booth fan off (but of course I wear a good respirator).

Note that this type of spraying results in more water being absorbed into the ware. Especially for thin pieces, care needs to be taken not to overload the ware with water. I usually spray the outsides one day and the insides the next, giving the ware sufficient drying time in-between sprays.

If while spraying you notice the glaze stays wet and shiny on the surface it means you are either spraying too close or have already reached saturation. This is bad. There’s a good chance that the entire glaze layer will separate from the ware.

My air compressor is actually just a cheap fish tank pump. It’s much quieter than normal air-tank compressors.

Detail of the 520W fish tank magnetic air pump, rated at 0.04MPa (approx 6PSI)

The spray canister is attached via rubber hose. A shut-off valve to controls air flow.

Mouth sprayers

The glaze sprayers widely used in Jingdezhen were originally meant to be sprayed using only one’s mouth. Since then, the mouth stem has been modified from conical (larger end towards mouth) to tapered at both ends for a tight fit into an air compressor hose.

Making these sprayers is a specialized craft. The sprayers come in dozens of different configurations. The sizes of the container, nozzle, and mouth stem as well as the distances between these parts, all determine the characteristics of the spray pattern. In general, larger containers are used for larger work (e.g. sculpture), while the smallest containers are used for spraying underglazes and details.

The parts that make up a glaze canister.

Some of my locally made glaze spraying canisters

Comparing spray patterns. On the left, Paasche L Sprayer #4 attached to air-tank compressor, approximately 30-40 psi. On the right, Jingdezhen glaze canister with fish-tank magnetic air compressor.

The Paasche L Sprayer #4

Like Jingdezhen glaze canisters, the Paasche allows you to make fine adjustments in distance between the nozzle and container tube. Along with adjusting air pressure and glaze thickness, a number of different spray patterns can be achieved.

Spraying

It’s difficult to write about actually spraying glaze, because each session is different. The basic process is:

- Spray outsides. Do not rest ware directly on turntable or plaster disc, but rather elevate it with a stable item such as a smaller plaster column. If the inside is already glazed, on top of the support you can add a sponge disk.

- After spraying the bottom, you can scrape glaze off of the feet.

Ideally, wait one day while the bottoms dry completely. If in a rush, blow air over the ware with a fan. - Spray insides. Take care that feet are not resting on a surface that will become wet during glazing. The dry plaster turntable disk helps with this issue.

- Clean glaze off the feet by trimming or with a sponge.

To spray:

- Using a notch in the turntable disk as a guide, keep a mental note of how many revolutions you make and the resulting thickness of the glaze (checked by scraping). The number of revolutions will vary each glaze session, and is influenced by the glaze canister, air pressure, glaze consistency, size of ware, etc.

- Keep the glaze canister in constant, steady motion- up & down, side to side, or circular. You may need to vary the motion to get consistent application.

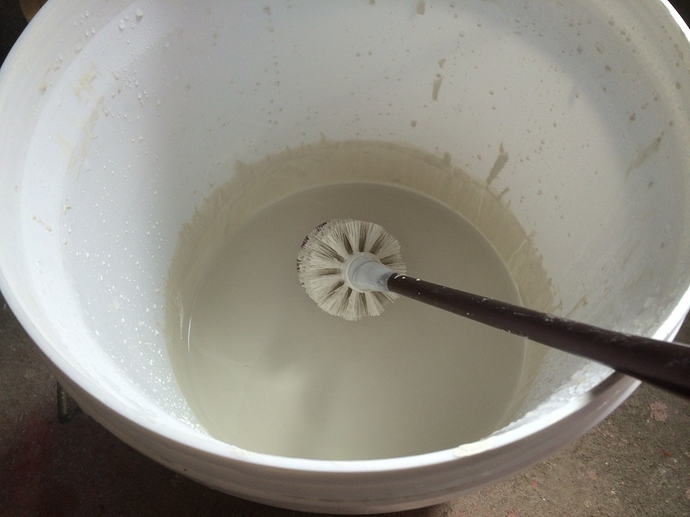

Using a toilet brush for mixing up the glaze each time I fill the canister

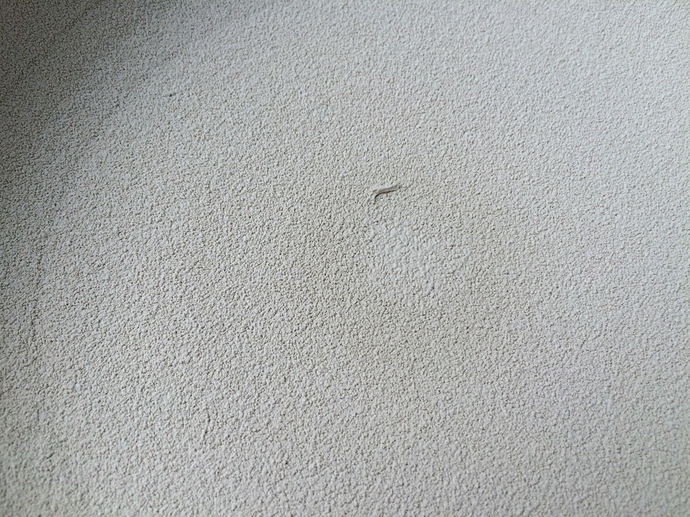

It’s difficult to see in this photo, but the center of this dish was trimmed thin, and the sprayed glaze has saturated the ware. The surface of the glaze is no longer powdery. Stop spraying.

I’ve found no consistent way to check glaze depth other than scraping with a knife.

After spraying the bottom, glaze can be scraped off with a box cutter blade or metal rib. Take care not to scratch the ware.

After spraying the bottom, a board is placed on the foot, then flipped over and placed on a ware board.

A large circular piece of foam is used to flip over glazed ware, protecting the insides.

Ware is placed on a damp, firm foam pad and rotated using even pressure, resulting in a clean glaze line.

Foam after cleaning a bottom. Foam firmness and hand pressure determines glaze line height.

Another method for creating a clean glaze line- using a notched rib.